Voyaging Beyond Horizons: Tonga's Seafaring Tradition and Island Connections

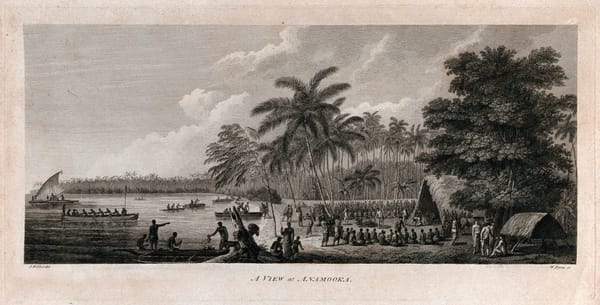

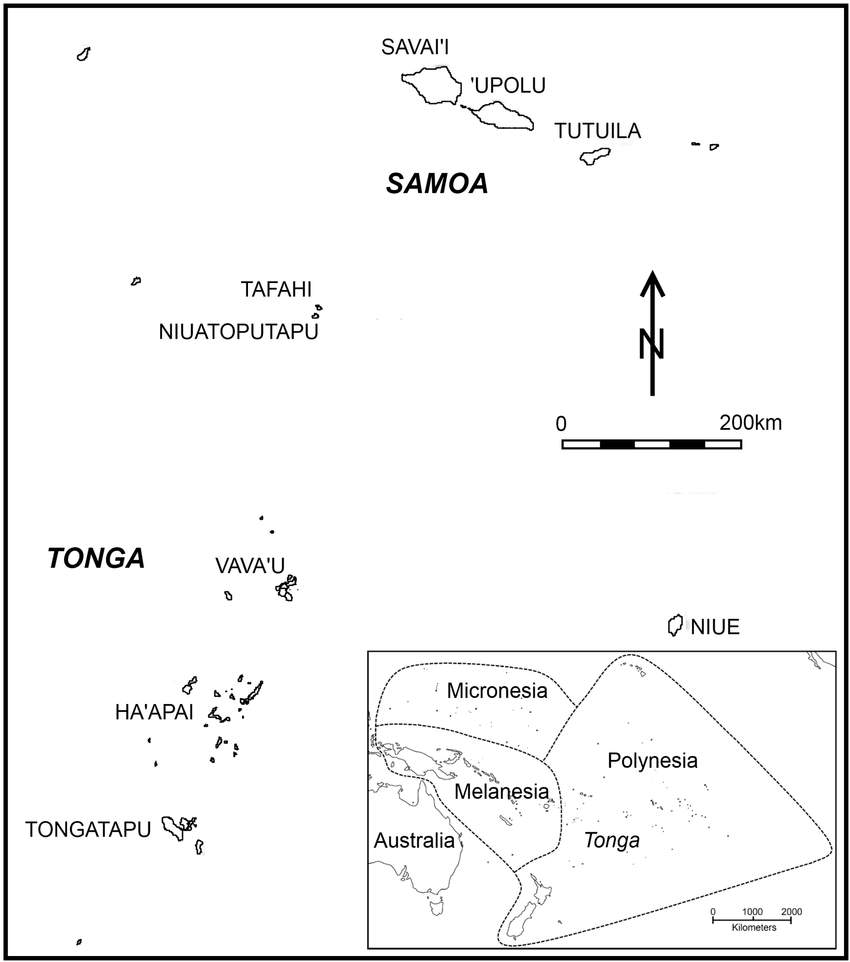

The contemporary realm of Tonga encompasses approximately 150 islands spread across an expanse of 32,000 square kilometers in the central Pacific Ocean. Positioned between 1° and 2° 30' south latitude and 170° to 177° west longitude, the Tongan islands occupy a central location in western Polynesia. Despite the apparent distance between island groups, regular interactions among their inhabitants played a significant role in shaping the history of each community, considering the broader regional context.

Geographically and historically, the Tongan islands are divided into three archipelagoes: the Tongatapu-‘Eua group in the south, the Ha‘apai group located 175 kilometers north and slightly east of Tongatapu, and the Vava‘u group approximately 100 kilometers northeast of Ha‘apai. Outlying islands like Niuatoputapu and Niuafo‘ou lie to the north and northwest of Vava‘u, with the now uninhabited island of ‘Ata southwest of ‘Eua. Although the islands share cultural and linguistic homogeneity, the dialectic variations of Niuafo‘ou hint at past affiliations with neighboring Samoan islands. Since the era of Tu‘i Tonga Kau‘ulufonuafekai, these archipelagoes have loosely formed a larger Tongan configuration, witnessing fluctuating political ties while maintaining strong kin relationships.

Inter-island and inter-archipelago communication in western Polynesia played a vital role in sustaining political and social relations. The Tongan islands, strategically positioned amidst favorable wind and sea currents, facilitated sailing routes. Tonga, situated south of significant anticyclones and well within the southeast trade wind belt, experiences consistent east-southeast winds from May to November, becoming more southeasterly from July. While December to April witnesses less reliable winds, Tonga still encounters favorable conditions for sailing, except for occasional violent squalls or cyclones known as "afa."

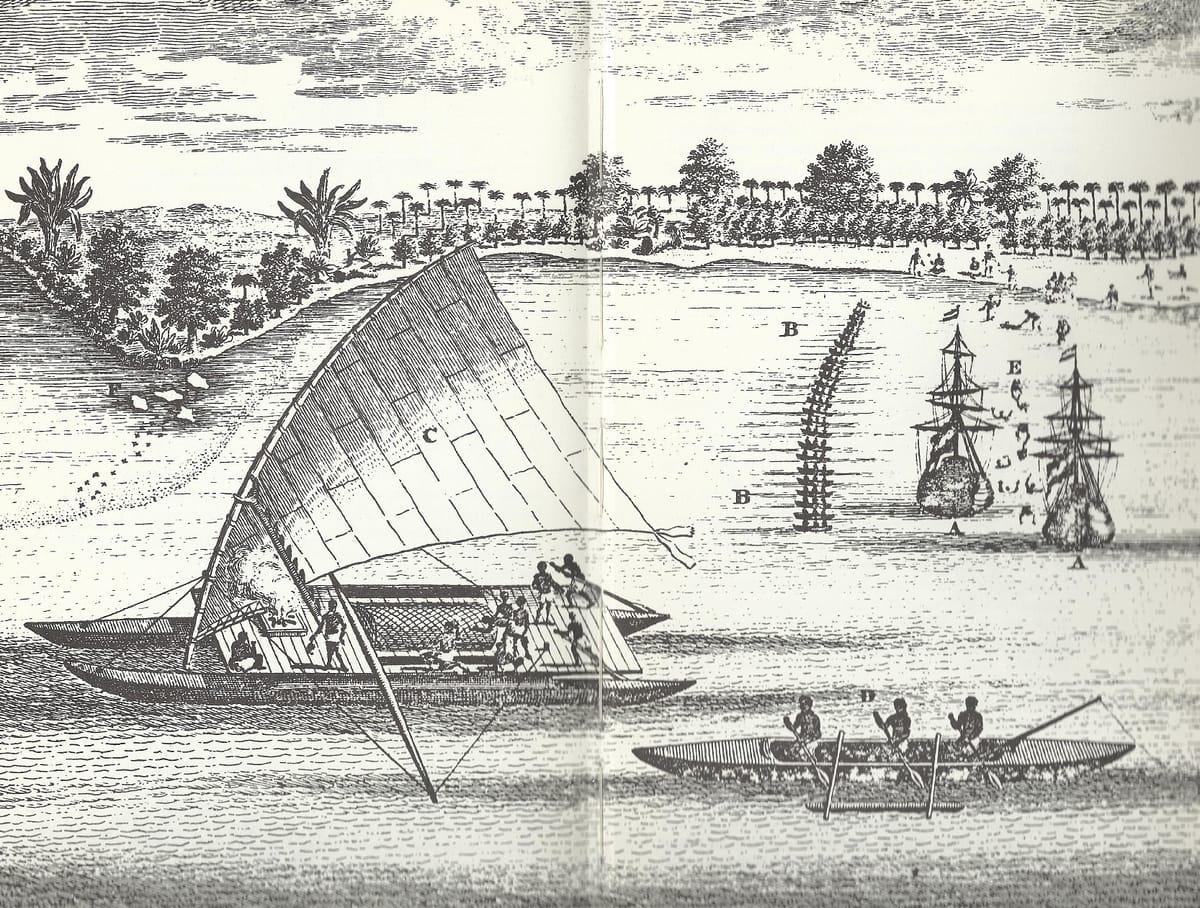

Long sea voyages were undertaken on double-hulled canoes, primarily of two types: the tongiaki and the kalia. The tongiaki, with a platform across its two hulls housing shelter and fireplace, posed limitations in beating to windward. The kalia, a design akin to the Fijian drua, offered superior speed and maneuverability, eventually replacing the tongiaki in long-distance voyages.

The construction and command of these advanced vessels were reserved for the Tongan elite, necessitating substantial investments. Tongan elites, lacking adequate wood resources, supported Tongan artisans in Fiji during the lengthy construction period. These endeavors involved presentations to Fijian chiefs, exchanging prestigious goods such as whale's teeth, ngatu, kie hingoa, and other luxury items.

Voyaging between Tongan islands was relatively straightforward, especially during southeast trade winds. However, longer and riskier voyages to Samoa and Fiji were common, involving strategic stops for refreshment. The return voyages, particularly from Fiji, were challenging and required adept maneuvering to catch favorable winds.

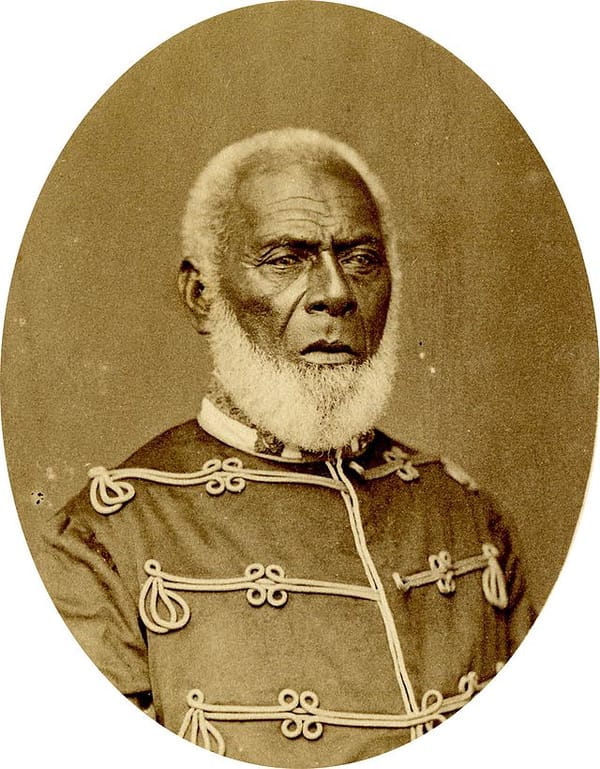

Despite occasional dangers, Tongans maintained frequent communication through extended visits for various reasons such as ceremonies, family events, and social interactions. The extensive travels of chiefly individuals became a point of concern for Wesleyan missionaries, who encouraged them to stay home and engage in spiritually profitable pursuits. Voyages to Samoa and Fiji, though perilous, were part of Tonga's historical and cultural tapestry, showcasing the resilience and seafaring prowess of its people.